Food and the environment: how what we eat impacts the planet

This spring, the Scottish Food Coalition has been busy hosting events on different topics related to food. At the end of May, the RSPB, on behalf of the coalition, hosted an event in Scottish Parliament on ‘Food and the Environment: How what we eat impacts the planet’.

We are all aware that the impact of our food system on the natural world is complex. Many factors including farming method, where food is grown, what pesticides and fertilisers are used, what is fed to our livestock, and so on, affect the environmental impact of the food we buy and eat. Professor Tim Benton, food researcher from the University of Leeds was our invited expert to shed some light on some of these issues. Professor Benton is Dean of Strategic Research Initiatives at the university, as well as a Distinguished Visiting Fellow at the Royal Institute of International Affairs at Chatham House. Until 2016, he was the Global Champion for the UK’s Food Security Programme.

Professor Benton’s talk was inspiring and terrifying in equal measure. Seen from both an environmental and public health point of view, he outlined why our food system needs to change, and rather fast at that.

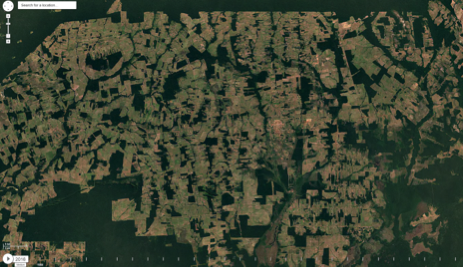

While we have been quite good at increasing yields to feed our ever-growing populations, we have done so largely without regard for the consequences. Water and air pollution, loss of wildlife, and of natural habitats all result from food production. With increasing production also comes increasing land use; below are two photos of the same area in the Amazon. The one above is from 1986 – the one below, from 2016, illustrating the loss of forest over the past thirty years.

We are all aware that the impact of our food system on the natural world is complex. Many factors including farming method, where food is grown, what pesticides and fertilisers are used, what is fed to our livestock, and so on, affect the environmental impact of the food we buy and eat. Professor Tim Benton, food researcher from the University of Leeds was our invited expert to shed some light on some of these issues. Professor Benton is Dean of Strategic Research Initiatives at the university, as well as a Distinguished Visiting Fellow at the Royal Institute of International Affairs at Chatham House. Until 2016, he was the Global Champion for the UK’s Food Security Programme.

Professor Benton’s talk was inspiring and terrifying in equal measure. Seen from both an environmental and public health point of view, he outlined why our food system needs to change, and rather fast at that.

While we have been quite good at increasing yields to feed our ever-growing populations, we have done so largely without regard for the consequences. Water and air pollution, loss of wildlife, and of natural habitats all result from food production. With increasing production also comes increasing land use; below are two photos of the same area in the Amazon. The one above is from 1986 – the one below, from 2016, illustrating the loss of forest over the past thirty years.

Source: GoogleEarth Engine, from Benton, T.G. (2017). Food and the Environment: How what we eat impacts the planet. Talk at the University of Edinburgh, May 30th, 2017.

And what about climate change? Around one-third of global greenhouse gas emissions come from agriculture[1], so our food system needs to take a big role in tackling climate change. But not only does food production have a hand in the problem, it is also very vulnerable to its effects.

Currently 86% of the food we eat comes from wheat, rice, maize, sugar, barley, soy, palm and potato. Around the world our diets are becoming increasingly similar, both in the food types, and also the varieties of those food types that we eat. This leaves us vulnerable to food crises if one of our global breadbaskets fails. The global food crisis of 2007/8 was caused by a yield loss in Australia of just a fraction of 1% of global food supply, but it led to spikes in food prices and political and social instability in parts of the world.

Add to this the large-scale food waste, and a double global health crisis of obesity and undernourishment, and it is clear that we are facing a systemic problem. But thankfully, Professor Benton came armed with some solutions. Ultimately, we need to diversify the things that we grow and where it is grown to create local food economies, and allowing imports and exports to supplement, rather than sustain food supplies. This does not mean we want to go back in time, but that we want to grow more food in Scotland that we want to eat in Scotland, and eat more of what we already produce.

This will also mean some pretty big changes in the way we govern the food system. Departments in charge of health, agriculture, social security, the environment, trade and so on need to work together to meet many different goals, rather than pursuing different agendas. The Good Food Nation Bill is our chance to change the way we do things in Scotland. We need to be bold and creative, and truly work together to rethink food altogether. We should value its producers, and help them do things better for the natural world; we should value the food, and be mindful of where it comes from and what it does to our bodies; and we should value our food culture, sharing good food with the people around us.

[1] https://www.nature.com/news/one-third-of-our-greenhouse-gas-emissions-come-from-agriculture-1.11708

And what about climate change? Around one-third of global greenhouse gas emissions come from agriculture[1], so our food system needs to take a big role in tackling climate change. But not only does food production have a hand in the problem, it is also very vulnerable to its effects.

Currently 86% of the food we eat comes from wheat, rice, maize, sugar, barley, soy, palm and potato. Around the world our diets are becoming increasingly similar, both in the food types, and also the varieties of those food types that we eat. This leaves us vulnerable to food crises if one of our global breadbaskets fails. The global food crisis of 2007/8 was caused by a yield loss in Australia of just a fraction of 1% of global food supply, but it led to spikes in food prices and political and social instability in parts of the world.

Add to this the large-scale food waste, and a double global health crisis of obesity and undernourishment, and it is clear that we are facing a systemic problem. But thankfully, Professor Benton came armed with some solutions. Ultimately, we need to diversify the things that we grow and where it is grown to create local food economies, and allowing imports and exports to supplement, rather than sustain food supplies. This does not mean we want to go back in time, but that we want to grow more food in Scotland that we want to eat in Scotland, and eat more of what we already produce.

This will also mean some pretty big changes in the way we govern the food system. Departments in charge of health, agriculture, social security, the environment, trade and so on need to work together to meet many different goals, rather than pursuing different agendas. The Good Food Nation Bill is our chance to change the way we do things in Scotland. We need to be bold and creative, and truly work together to rethink food altogether. We should value its producers, and help them do things better for the natural world; we should value the food, and be mindful of where it comes from and what it does to our bodies; and we should value our food culture, sharing good food with the people around us.

[1] https://www.nature.com/news/one-third-of-our-greenhouse-gas-emissions-come-from-agriculture-1.11708